Logging in Python

At some point in your project, you start realizing that print() statements aren't cutting it anymore. You need something that can record messages with context, standardize a format, route logs to different outputs, and scale beyond debugging in your terminal. Python comes with the built-in logging package to help with that, which is also the standard way to deal with logs in Python.

In this article we'll cover the essentials of this powerful and flexible package, as well as general concerns you need to keep in mind when working with logs.

The core components

When you log something in Python, several components get involved under the hood, in order:

- Log record: the actual data structure that holds all the log data

- Logger: this is the object your code uses directly (logging.getLogger()) to create a log a record

- Logger Filter: optionally decides whether a log should even be processed (passed to handlers)

- Handler: receives the log record and decides where to send it (file, stdout, syslog, external service, etc.)

- Handler Filter: same as the Logger Filter; runs after the handler receives the record but before it formats or emits

- Handler Formatter: defines how the log message will look and serializes the Python log object into a string

When a log record is created, it travels from the logger, through filters and to the handlers, until it is formatted and emitted. The diagram below maps out the cardinality of a single logger:

Logger

├─ Filters (0..n)

├─ Handlers (0..n)

│ ├─ Filters (0..n)

│ └─ Formatter (0..1)

Each named/custom logger you create, has a parent logger (by default the root one) and it can also have children loggers, if you use a.b naming, where a is an existing logger's name. There is no limit to the hierarchy of the loggers. Once a logger finishes sending the record to its own handlers, the logger passes the record to its parent logger, which then runs its handlers, if propagation is set to true. The forward propagation of a log record is always done by the logger, not handlers, formatters or filters.

This hierarchy is useful because it lets you enable or disable logging for entire layers of your application. In practice, though, you rarely need to build this whole tree from scratch. The root logger does a good job on its own. Nevertheless, you should often times avoid using it directly (more on that below).

Root logger vs custom loggers

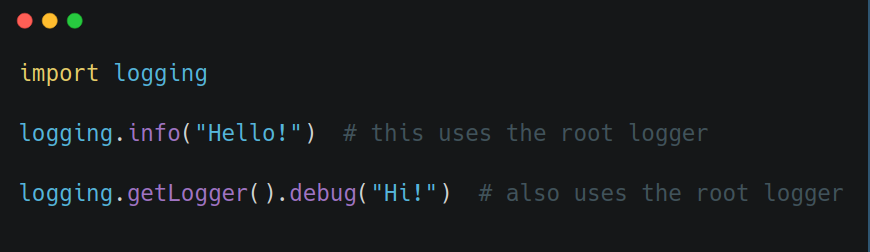

You can totally do something like this:

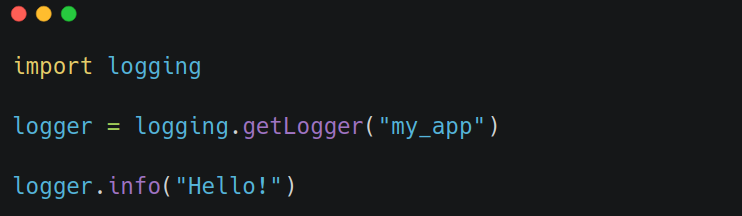

but it's better to create your own logger:

The main reason being, the root logger is shared by everything, including third-party libraries. If you change its level or format, it might mess up their logs too. Having your own logger makes sure you don't mess with anything you shouldn't, and it gives you finer control on your custom logs.

One named logger, defined in your application's entrypoint module, is fine. In larger projects, you can use a logger per package (i.e. getLogger("src.db")).

Using __name__ for module-level loggers is common, and it's something I'm guilty of too, but it's often not optimal. This is especially true in large codebases and long-running apps (i.e. BE API) where loggers are global objects. Keeping in memory a logger object for each Python module of your application, during its entire lifespan, is overkill. A simpler structure with package-level loggers is probably easier to reason about.

Logging config

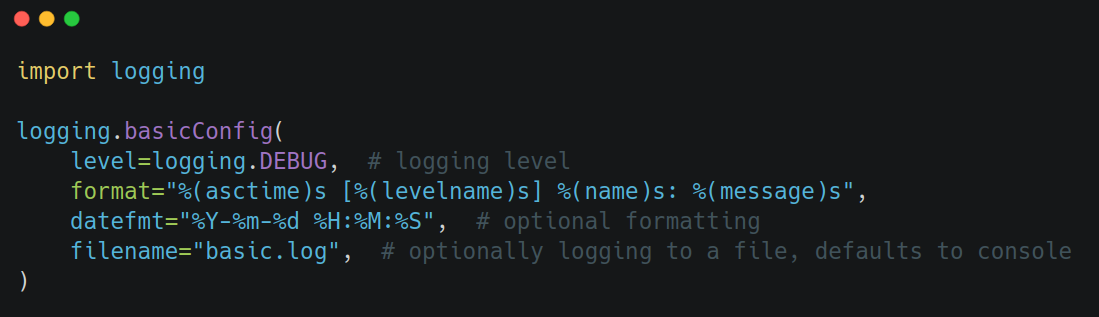

For small applications or quick prototypes, you can configure logging easily using basicConfig(). This sets up the root logger with default handlers, level, and formatting.

This affects only the root logger in a direct way. Indirectly, it will affect all custom loggers too, regardless of whether they are created before or after the basicConfig() call, as long as they dont define their own handlers, and allow propagation. That's because under those conditions, custom loggers offload the job to the root logger. Any subsequent call to logging.getLogger() after this will use the same base configuration, because again, it gets the root logger. That is, until you call basicConfig(force=True) again (which overrides the previous setup). Not explicitly passing the force argument, will change nothing, if the root logger already has a handler. If that sounds a bit confusing, that's because it is. Go over it 1-2 more times and it will click.

Note that if you need to customize the logging configuration for a specific logger instance, you can still do so anytime using the methods of logging.Logger like addHandler and setLevel. But by setting up the default configuration with logging.basicConfig, you can ensure that all of your logger instances start with the same basic configuration unless explicitly configured otherwise.

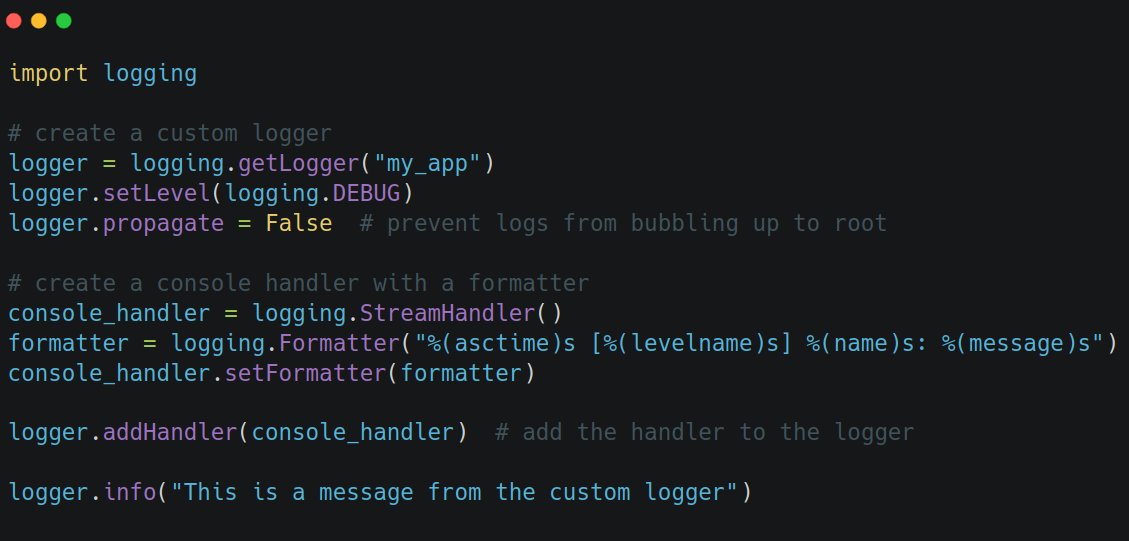

That being said, for reasons explained in the sections above, in larger applications it's better to create a dedicated logger for your application, attach handlers, and control propagation explicitly:

You'll likely eventually want to use logging.config.dictConfig instead, for loading up more complex configurations. Especially if you go with structured logging (see section below).

Logging levels

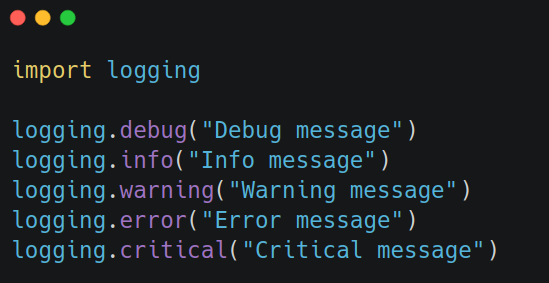

Logging comes with five standard severity levels:

If you set the logging level to WARNING, only warning, error, and critical will appear. Each level includes itself and the more "serious" levels above it. The default level is WARNING.

The different logging levels are used not only to mark the severity of a log event, but also to control the verbosity. In any application or third-party package, you'll likely find a lot more DEBUG or INFO statements, rather than CRITICAL. That way, if you're in a debugging session, you can temporarily set the level to DEBUG, to understand more about how the application is behaving. And once done, switch it back to INFO, as you don't want all that noise to continue. The logging verbosity affects the logs volume, which in turn may affect logging retention and pricing, especially when using third-party logging services, so it's something to keep in mind. The logging level, at least the one you define when you call basicConfig(), should be controlled via an environment variable.

By default, Python logs WARNING and above to stderr, and the rest to stdout. Depending on the config though (see above), you may not log to standard IO streams at all, or decide to send everything to stdout.

Structured logging

By default, log statements look something like this:

format="%(asctime)s [%(levelname)s] %(name)s: %(message)s"

But in production systems, it’s usually better to log in a structured format. Structured logging is about representing log data in a way that preserves its fields and types, making logs also easier to parse, read, and query. This is especially important if you are going to feed those logs into third-party logging services like ELK or Datadog, which you should.

By doing structured logging, in ElasticSearch we'd end up with a document with fields, who are indexed, have field mappings, and can be efficiently queried. This is much better than having one big string field called message containing everything; we'd have to resort to string parsing to be able to extract valuable information.

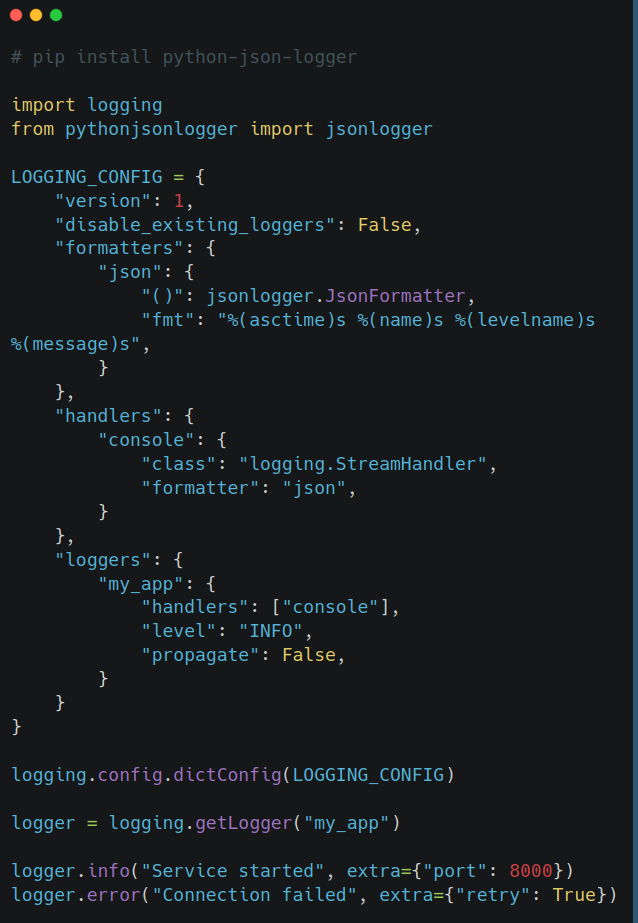

A common example of a structured logging format is JSON. Python doesn’t come with a JSON formatter out of the box, but you can build one or use libraries like python-json-logger. When doing so, you typically output JSON Lines that would look like this:

{"timestamp": "2025-11-09T12:00:00Z", "level": "INFO", "name": "my_app", "message": "Started service"}

{"timestamp": "2025-11-09T12:00:01Z", "level": "DEBUG", "name": "my_app", "message": "Listening on port 8000"}

In JSON Lines (.jsonl) format, each line is valid JSON, even though the overall text file/stream is not. And the logs are parsed line by line. In the example above, we have 2 lines, and each line is a log record and separate JSON object.

Here's how you would do something like this:

JSON is a popular format because it’s structured and widely supported. But structured logs can also be protobuf, Avro, or any schema-based format. The idea is that the log is machine-readable, not just human-readable.

Logging and performance

A generally overlooked aspect of logging, is that each log statement involves I/O: writing to a file, sending data over the network, etc. If you’re logging heavily inside an HTTP request handler for example, those I/O operations can pile up fast and impact performance.

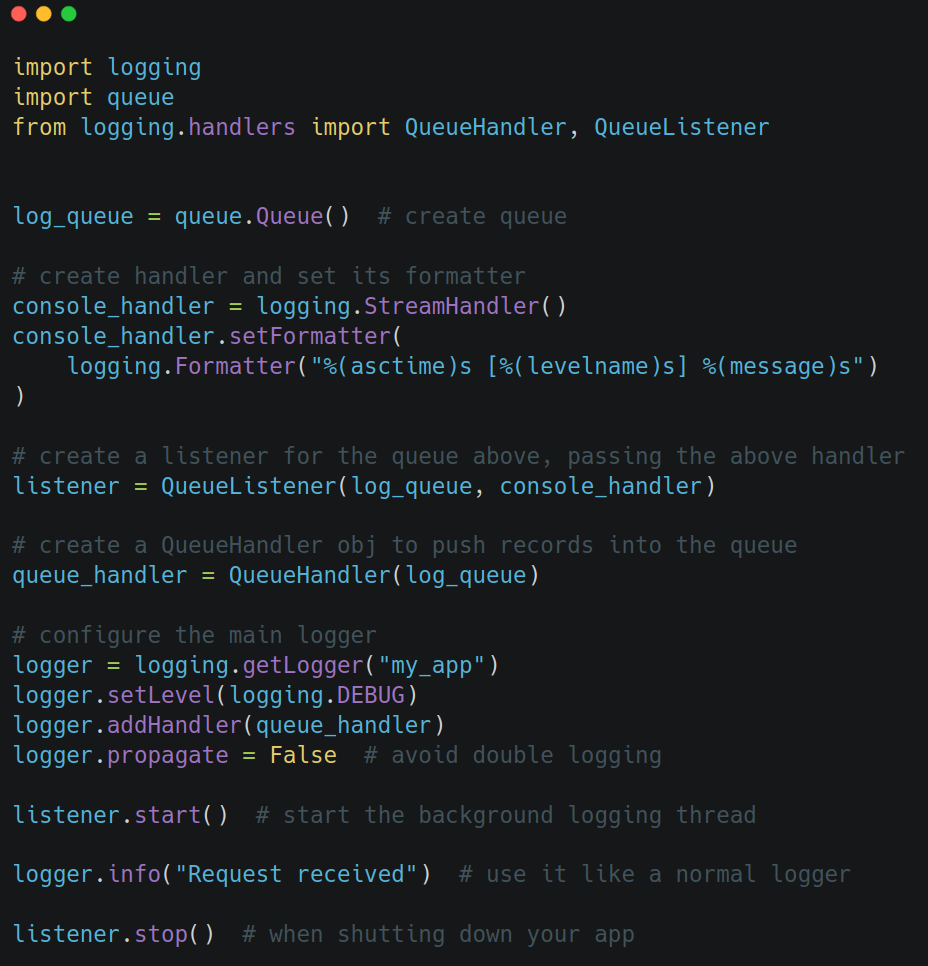

A better approach is to use a QueueHandler and QueueListener:

- the handler writes logs to an in-memory queue (non-blocking)

- the listener runs in a separate thread and actually processes them

Building the log record isn't the slow part; sending it where it needs to go, is. Essentially, the I/O part. And a queue handler stores the log records in a queue without blocking, while an associated queue listener reads those messages and passes them to a handler in another thread. That way, the main thread can keep running while logs are flushed asynchronously.

To set it up like this, you need to define a queue handler in your config, and also start the listener's thread when the app runs:

This is arguably overkill though, for many projects out there that don't operate in performance-critical territory. The main takeaway is that logging will do I/O, so each log statement comes at a cost. If you need to log out a lot, the above setup is reasonable. Otherwise, keep logs sparse and at the appropriate logging level, and/or be smart with the filters. You don't want to needlessly produce a ton of logs.

Final notes

A few more notes and tips on working with logs:

- logger.exception() automatically includes the stack trace if inside an except block, so you don’t need to pass exc_info=True manually

- logger.error() needs exc_info=True to include the stack trace; use exception() for that, and keep error() for errors that don't map to an exception in the code but are nevertheless errors semantically

- when you're handling a low-level exception and want to raise a higher-level one, use raise X from e to preserve the original context by chaining the exceptions; this adds important context to the logs

- using f-strings in log calls evaluates the string even if it’s never logged; prefer lazy formatting with %-strings

- don’t log sensitive information such as credentials, tokens, PII; it’s a common security vulnerability

This should cover the essentials needed for logging in Python. With this, one can build a complex logging solution, as there's many advanced and cool things you can do with structured logging, multiple complex filters, external logging services, alerts, logging hierarchy, etc.